Policy Impact

China: National Air Quality Action Plan (2013)

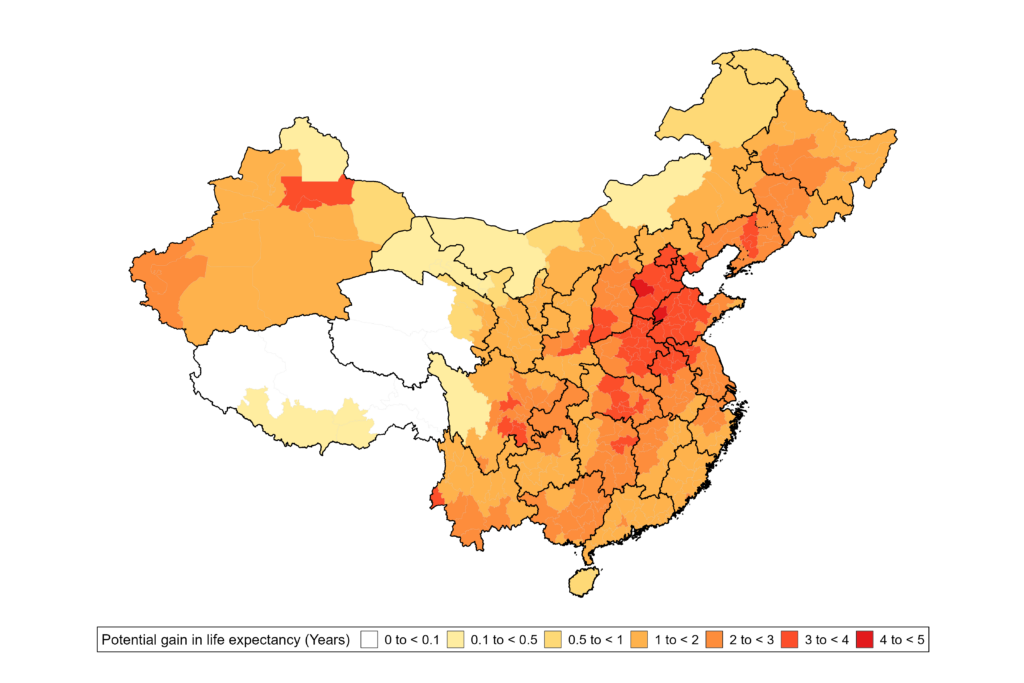

In 2021, after eight years of fighting a “War against Pollution,” China has seen remarkable progress in reducing pollution and it is winning its war. If these improvements are sustained, and the pollution is further brought down to the levels prescribed by WHO, people in China could see their average life expectancy increase by 2 years.

Over the last few decades, China has gained a reputation for being one of the most polluted countries in the world. Yet, it hasn’t been in the top five since 2016. Indeed, air pollution is a challenge for China, but the country has made remarkable progress in reducing its pollution in recent years thanks to a series of decisive actions taken after intense public scrutiny.

Public concern about worsening air pollution began mounting in the late 1990s. In 2007, Ma Jun, director of China’s path breaking environmental NGO, the Institute of Public & Environmental Affairs, released the China Air Pollution Map, a tool that allowed users to view air quality data from around the country. Beginning in 2008, the U.S. embassy in Beijing began publicly posting readings from its own air quality monitor on Twitter and the State Department website, which residents quickly pointed out conflicted with the level of air quality reported by the city government. By 2012, the U.S. consulates in Guangzhou and Shanghai also had set up their own pollution monitors and began reporting data.

Then, in the summer of 2013, EPIC Director Michael Greenstone and three co-authors published a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that found high air pollution had cut the lifespans of people living in northern China short by about five years compared to those living in the south. The clear demonstration of the health impacts further galvanized public scrutiny and drew the attention of the environment ministry.

Soon after, reports began to circulate of foreigners leaving the country due to health concerns, just as China experienced some of its highest concentrations of fine particulate matter pollution (PM2.5) on record with little reason to believe conditions would ever improve. In the country’s capital city of Beijing in 2013, for example, the average PM2.5 concentration was seventeen times the amount the World Health Organization (WHO) considers safe, and 2.4 times the country’s own Class 2 national standard. In January of 2014, pollution monitor readings reached 30 to 45 times recommended daily levels, and city officials warned residents to stay indoors. Similarly, in Shanghai, the annual average concentration was 9.1 times the WHO standard. Across the entire Chinese population, the average resident was exposed to a PM2.5 concentration of 52.4 µg/m³, which corresponds to a decline in life expectancy by 4.6 years.

“The average resident was exposed to a PM2.5 concentration of 52.4 µg/m³, which corresponds to a decline in life expectancy by 4.6 years.”

The Policy

Amid one of the worst stretches of air pollution in modern Chinese history, Premier Li Keqiang declared a “war against pollution” at the beginning of 2014 during the opening of China’s annual meeting of the National People’s Congress. The timing of the declaration—at the kickoff of a nationally televised conference typically reserved for discussing key economic targets—marked an important shift in the country’s long-standing policy of prioritizing economic growth over concerns about environmental protection. It also marked an important change in the government’s official rhetoric about the country’s air quality. In the past, state media had deflected concerns about air quality by claiming poor visibility was due to “fog” and that emissions had no effect on levels of smog. Now, the government stressed environmental responsibility, stating the country could not “pollute now and clean up later” and would fight pollution with “an iron fist.”

The declaration followed the release just months earlier of the National Air Quality Action Plan, which laid out specific targets to improve air quality by the end of 2017. The Plan set aside $270 billion, and the Beijing city government set aside an additional $120 billion, to reduce ambient air pollution. Across all urban areas, the Plan aimed to reduce PM10 by at least 10 percent relative to 2012 levels. The most heavily-polluted areas in the country were given specific targets:

- Reduce PM2.5 in the three target regions of Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta by 25, 20, 15 percent, respectively.

- Reduce annual PM2.5 in Beijing by 34% from the 2013 level

The government’s strategies for achieving these goals included:

- Build pollution reduction into government officials’ incentives so promotions depended on both environmental audits and the economic performance of their jurisdictions. Provincial and local officials are now incentivized to improve the environment in their jurisdictions.

- Prohibit new coal-fired plants in the 3 target regions and require existing coal plants to reduce emissions or be replaced with natural gas. In 2017, Shanxi province, China’s largest coal producer, shut down 27 coal mines. By January 2018, Beijing had closed its last coal-fired power plant and the national government canceled plans to build 103 more.

- Increase renewable energy generation. Renewable sources made up more than a quarter of energy generated in China in 2017. In comparison, they made up just 18% of the U.S. energy generation that year.

- Reduce iron and steel making capacity in industry. Between 2016 and 2017, China shut down 115 million tons of steel capacity, and further cuts are planned.

- In large cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, control vehicle emissions by restricting the number of cars on the road on any given day. Each of these cities has a quota on the number of new license plates issued each year, capping the number of cars on the road.

- Better enforce emissions standards. In late 2017, China suspended the production of 553 car models that do not meet fuel economy standards, including ones made by foreign and state-run companies.

- Increase transparency in government reporting of air quality statistics. China has built a nationwide network of air pollution monitors and makes the data publicly available. By March 2017, there were over 5000 monitoring stations in China.

- Due to these actions, all the targets set by the National Air Quality Action Plan, which expired in 2017, were met. China’s government, however, remained acutely aware that the country’s air pollution was still a serious problem. To achieve further improvements, the Chinese government announced in July 2018 a new plan for 2018-2020. Regions that did not meet the national air quality standard of 35 µg/m3would need to reduce particulate pollution by 18 percent relative to 2015 levels. Though the national targets are less ambitious than those set for 2013-2017, some prefectures set more stringent targets for themselves in their local five-year plans. For example, Beijing committed itself to a 30 percent reduction from 2015 levels by 2020 and as per the latest satellite data, it ended up reducing pollution by 55.5 percent in this period.

- These aggressive targets have come with some unintended consequences. For example, in the winter of 2017-2018 officials began <a “href=”https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/10/world/asia/china-coal-smog-pollution.html”>removing coal boilers used for heating from many homes and businesses even though replacements were not yet available everywhere. This left some without heat. Those who were connected to natural gas lines saw their prices surge because of the undersupply. For China, work remains not only in sustaining and furthering its pollution reductions, but also in aligning incentives, market structures and local realities to smooth transitions to cleaner options.

The Impacts

The Chinese government’s air pollution reduction strategies have largely allowed the country to win its war against pollution. Between 2013 and 2021, particulate pollution exposure declined by an average of 42.3 percent across the Chinese population. If that reduction is sustained, it would equate to a gain in average life expectancy of 2.2 years. The decline in global average pollution since 2013 is due entirely to China’s success in reducing pollution. China was among the ten most polluted countries in the world each year from 1998 to 2019 but fell out of the top ten in 2020. The Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei area, one of China’s most polluted areas in 2013, saw a 53.1 percent reduction in particulate pollution, translating to a gain of 4.4 years of life expectancy for its 109.2 million residents, if sustained.

To put the scale and speed of China’s progress into context, it’s useful to compare it to the United States and Europe after their periods of industrialization. In the United States, following the passage of the Clean Air Act, it took almost three decades and five recessions to achieve about the same percent decline. In Europe, after their environment agency was created, it took about two decades and two recessions to achieve approximately China’s percent reduction.

Despite tremendous progress over the past few years, China is still the 13th most polluted country in the world. As a comparison, particulate pollution in Beijing is still 40 percent higher than the most polluted county in the United States (Plumas county in California). Even though China’s overall particulate pollution average is in compliance with the national standard, 30.9 percent of the population still lives in areas that exceed the national standard of 35 µg/m3. If these areas were to comply with the national standard, it would result in a gain of 216.7 million total life years. An individual living in these areas would gain 6 months of life expectancy on average if the pollution was brought down to the levels prescribed by the national standard.

In China’s most polluted prefecture—Shijiazhuang in Hebei Province—the average person is on track to lose 4.3 years of life expectancy on average relative to the WHO guideline.

To this point, China has relied on command-and-control measures to swiftly reduce pollution. While the measures have worked, they have come with significant economic and social costs. As China now enters the next phase of its “war against pollution,” the long-run durability of its actions will be enhanced by minimizing the costs. Relying on market-based approaches (e.g. an emissions trading scheme) is a possible solution that can effectively and inexpensively reduce pollution.